Go to the list of questions ->>>

This has not been an easy summer for students and their families. After a stressful end to the school year, with lockdowns, homeschooling and the A-level fiasco, students and parents are of course anxious to know what the coming year will look like. Unfortunately, we don’t think that universities have been transparent with students and parents throughout this process. Warwick Anti-Casualisation is a grassroot group advocating for PhD-students and Early Career Academics, who deliver a majority of the teaching at the University of Warwick. We have been teaching in various departments across the university, and we are concerned for our students and colleagues who are expected to return to the classroom in a couple of weeks, as well as the broader Coventry community. As such, we would like to offer our perspective on some questions that we have seen make the rounds in social media and universities’ communication.

In short, we don’t think that universities have been working hard enough to make campus a safe environment for students, staff, and surrounding communities. We therefore support the call made by the University and College Union (UCU) and its local branches to make online teaching the default option this term. This demand has also been voiced by Warwick Students’ Union and our local Member of Parliament, Zarah Sultana.

We do not take this position lightly. We love teaching and interacting with students. We also do not think that online teaching is the perfect alternative but it’s the only one that is currently safe. Even with in-person teaching, the “student experience” advertised by universities such as Warwick will not materialise in a safe, physically distanced setting. As of mid-September, the existing plans of many universities, including Warwick, are unclear or they do not reflect the reality – which is that neither physical distancing or appropriate ventilation is achievable with the current infrastructure in place on campus. These plans also come in a context of massive job cuts during the pandemic, in which fewer teaching staff have been hired for the 2020-21 academic year. Meanwhile, remaining staff members had been overworked long before the Corona-crisis began.

Going forward with in-person teaching puts the health of students and staff at risk, but also that of the wider communities in which we live and work. We had long discussions about these topics and put together some answers to questions students and their families may be asking themselves when hearing the calls by student and staff unions to move teaching online this term. The context in which we are publishing this document is in a state of flux, with universities and the government regularly changing their guidance and updating their plans. The following responses reflect our understanding of the situation as of 15/09/2020.

QUESTIONS:

Universities have made a commitment to in-person teaching. Why are you against it?

How does in-person teaching affect the local community?

University students are grown-ups and can follow the rules and be careful! Why do you believe there is still a risk?

Universities have had all summer to prepare safe teaching environments. Has this not been successful?

Schools are reopening, why shouldn’t universities ? Are the risks any different?

Key workers in retail, healthcare, transport and more have been working in person throughout the pandemic. Why shouldn’t university staff?

Universities have been closed since March, why do you not want to go back to work?

Are teaching staff just trying to cut corners by teaching online?

Isn’t in-person teaching a better experience for students?

What about activities that can’t take place online, like labs and practical classes?

Why don’t you find a better way to split the workload among staff to allow for safe in-person teaching?

Warwick is a campus university; shouldn’t that make it safer?

Wouldn’t online-only teaching mean massive job losses at universities?

You mentioned casualised teachers. What does casualisation mean, and how does it affect me?

Universities have made a commitment to in-person teaching. Why are you against it?

We cannot tell the future – however, we can listen to experts and draw lessons from what has happened in other countries. The Government’s SAGE committee has warned that ‘there is a significant risk that Higher Education (HE) could amplify local and national transmission’, and Independent SAGE recommended that ‘all University courses should be offered remotely and online, unless they are practice or laboratory based, with termly review points’ to protect the safety of students, staff, and local communities.

Universities in other countries, which have already re-opened, have illustrated how fast Covid-19 cases spread. The United States campuses offer a glaring example. On 31 August, CNN reported 8,700 new cases in 36 states, only a couple of weeks after universities reopened. Though the US and the UK are not fully comparable, what happened there should alert us to what can happen here.

We fear that the mass movement of students already underway and their attendance of in-person seminars pose a great health risk to students, staff, and the broader university community. We also believe that the measures taken by the University are insufficient. Colleagues are expected to teach in windowless and poorly-ventilated classrooms, when the Government’s guidance states that ‘poorly ventilated buildings are particularly conducive to virus spread.’ Meanwhile, the University of Warwick’s own testing facility is only open to students living on campus who show symptoms, whereas asymptomatic people can spread the virus and 75% of students live off-campus. This leaves us unconvinced about the university’s plans to prevent or manage an outbreak.

In these circumstances, it is highly possible that teaching will have to be shifted online anyway after a few days or weeks if cases rise – as has happened in the US. In fact, staff were told to prepare for the move to online teaching, meaning that universities are aware of this likely scenario. Some UK universities, such as the University of St Andrews have recently announced the postponement of in-person teaching. We feel that waiting until the last minute to make this shift, instead of announcing a clear plan well in advance, is inducing anxiety and unnecessary financial burden among students – increased by the prospect of ending up under self-isolation or lockdown away from home at the start of term, or risking to infect their families by returning home.

In a nutshell, even though teaching staff prefer teaching in person in normal circumstances (Are teaching staff just trying to cut corners by teaching online? ), the pandemic and distanciation rules mean in-person activities will be very different this year (Isn’t in-person teaching a better experience for students?) and pose a serious threat to the health and safety of students, staff, and our local community (How does in-person teaching affect the local community?)

Go to the list of questions ->>>

How does in-person teaching affect the local community?

We care about the health of our colleagues and students, but the demand to move teaching online is not just about protecting them. It protects the broader community and reduces strain on our local hospitals, at relatively little cost for the university community.

Students and university staff do not reside in a bubble, but interact with the rest of the world – even in the case of campus universities such as Warwick (Warwick is a campus university; shouldn’t that make it safer?). Many live with friends or relatives, including people particularly vulnerable to Covid-19. Some live in areas affected by local lockdown measures and high infection rates. This means that in-person teaching, by increasing the amount, length, and frequency of interactions between people, heightens the risk that university students and staff may catch the virus, and that they may transmit it within the local community.

We are particularly concerned about the risks for key workers in our communities (Key workers in retail, healthcare, transport and more have been working in person throughout the pandemic. Why shouldn’t university staff? ). Bus and train drivers will be under increased stress with the mass movement of students in September and throughout the term, and so will supermarket workers. Hospital staff will be affected by a rise of cases in the area. Many students will be key workers themselves, working in supermarkets and elsewhere to finance their studies.

Go to the list of questions ->>>

University students are grown-ups and can follow the rules and be careful! Why do you believe there is still a risk?

Nobody can be trusted not to transmit the virus. We fear that even if most students strictly adhere to the rules set out by universities, this is unlikely to stop the virus from spreading. University accommodation is often crowded, and social distancing in shared kitchens is nearly impossible. The corridors in universities are narrow, and many seminar rooms are either too small or without sufficient ventilation to ensure that the virus does not spread. This is exacerbated by the daily movements of university staff and students, from commuting to and from work, to shopping in local supermarkets (How does in-person teaching affect the local community?). Moreover, given that asymptomatic people can spread the virus, we will not always know whether a student or member of staff is infected. If a student becomes infected, it is unlikely they will know before having already infected others in their flat or seminar groups. We want to prevent this from happening.

Not only do we not want to risk the health of students, staff, and communities. We also do not want students to be blamed for outbreaks and campus closures by university managers who did not do enough to ensure that campuses are safe to engage in in-person teaching. The current plans are vague or impractical, for instance those for Warwick students living in off-campus accommodation, meaning universities can easily blame an outbreak on students’ noncompliance. We do not want to see students vilified in the media or the government for an outbreak that was inevitably going to happen. We fear that this will be particularly directed at international students, considering the racism directed at them since March.

The choice to make in-person teaching the default option lay with senior university managements and the government: it was their responsibility to make campuses safe, and we do not think they have done enough. University managers and government officials should not blame the result of their own poor planning on students, nor on staff.

Go to the list of questions ->>>

Universities have had all summer to prepare safe teaching environments. Has this not been successful?

Most university staff have been working really hard to prepare for different scenarios – 100% in-person teaching, blended learning, 100% online teaching, etc. – as much as they could over the past few months. However, there has been a limit to what they could do before the academic year begins due to the ambiguous position of the senior management until the very last minute, as well as their unwillingness to inform, support, and negotiate with staff. Rather than investing into preparation and teaching, the sector has seen mass layoffs, especially for teaching staff.

Even in a normal year, many academic contracts only pay for 10 months, meaning staff are not paid during the summer – a period of time that many academics dedicate to their research activities. Others, especially casualised workers such as seminar tutors, have been told that they would not be employed for the next year and therefore could not prepare. Until now (mid-September), many do not know whether they will teach and if so, which classes, of which sizes, in which rooms, and in what conditions.

Go to the list of questions ->>>

Schools are reopening, why shouldn’t universities ? Are the risks any different?

As students from previous cohorts will already know, universities are a very different environment compared to schools – though the later face their own share of challenges in mitigating the Covid-19 pandemic. There are three main aspects that mean that the risks at universities are different from, and higher than, those at schools.

- Mass travel at the beginning of the academic year

Contrary to pupils and students at school who usually stay in their hometown, the start of the academic year sees millions of university students moving from all over the country – making up one fifth of all internal migration in England and Wales – and from abroad. If in-person teaching starts as planned, about 28,000 students will travel to the University of Warwick, all at once – and some have already arrived. Similarly, teaching staff on fixed-term contracts (a majority at Warwick) have to move every year, contributing to this mass migration.

- Mass travel during the academic year

While schools are often in the same neighbourhood you live in, this is usually not the case for universities. At Warwick, students travel daily from Coventry, Leamington Spa, Birmingham, or even further. For these students, campus is often only accessible by public transport. The buses and trains at peak times are often packed, meaning students are likely to encounter many people without the possibility to maintain social distancing and properly track and trace interactions. Current employment practices in Higher Education also mean that teaching staff have multiple contracts at different universities and travel long distances to get to various universities they teach at, multiplying the risks.

- Social bubbles are very difficult to maintain on a university campus

While universities and schools face similar challenges with regard to upholding social bubbles, as staff teach across subjects and year groups as well as with students interacting with different groups of people, these challenges are amplified at university. Not only are universities much larger, but student accommodations often house a larger number of people, who themselves interact with many different groups in their various seminars. At Warwick, we have not been made aware of a strategy to ensure the 7,000 students who live on campus are accommodated with peers they share classes with, which would be necessary to operate in a bubble system. This system would also be impossible to impose on students who live off-campus.

The risks are therefore, in our opinion, greater at universities than in schools. Providing online teaching to adult university students also creates significantly less practical difficulties than in the case of children unable to study independently and/or to be without supervision. Switching to online-teaching at university this term in the current circumstances therefore makes sense.

Go to the list of questions ->>>

Key workers in retail, healthcare, transport and more have been working in person throughout the pandemic. Why shouldn’t university staff?

Key workers deserve not only everyone’s heartfelt respect, but also improvement of working conditions, as well as substantial pay rises. They also deserve that the rest of the country acts responsibly and minimises the spread of Covid-19, in order to reduce the pressure they face in their jobs, at hospitals and supermarkets, in trains and buses. The past few months have demonstrated how much key workers have suffered from direct exposure to the virus, getting sick, having to shield their loved ones, and being forced to work to make ends meet. Preliminary research has also found that one of the contributing factors of BAME people having a higher infection rate is that they are more likely to be key workers. Many have had no choice but to attend their workplace in person, as their work cannot be done remotely.

In contrast, many university staff can work and teach remotely without significantly affecting the quality of studies of their students while protecting the health of everyone. We don’t want to contribute to spreading the virus, including to key workers, until there are sufficient measures to protect everyone.

Go to the list of questions ->>>

Universities have been closed since March, why do you not want to go back to work?

Despite how much senior management of universities, media outlets, or politicians keep saying that universities have been ‘closed’, most staff have never stopped working since the pandemic began. While colleagues have been furloughed and some precarious staff let go, many people across the university have worked remotely – often in difficult conditions and while caring for children or relatives. Many university staff haven’t been able to take annual leave, both because of workload and financial pressures. In a normal year, summer time and other periods outside of term, university staff are working: exam boards, admissions, administrative and logistical preparations are managed by colleagues at all levels of the university. Teaching staff use this time to catch up on their research activities (an important part of their job which they cannot perform during term-time) and prepare course content for the next academic year. This summer has been particularly difficult as modules needed to be completely re-designed in line with a ‘blended’ learning approach and lectures fully recorded and sub-titled (Universities have had all summer to prepare safe teaching environments. Has this not been successful?). It is not about ‘going back to work’, but about welcoming our new and returning students in the best and safest conditions.

Go to the list of questions ->>>

Are teaching staff just trying to cut corners by teaching online?

Organising online teaching is much more time-consuming than people think, especially when lecturers and tutors use it for the first time. Talking to a camera is by no means easier than talking to someone in person. As teachers we have been professionally trained to do in-person teaching throughout our career so everyone is working incredibly hard to make the shift in such a short period of time, often with varying degrees of content-creation literacy, lack of functional equipment and insufficient technical support. We cannot say whether creating online teaching materials will eventually help universities cut corners in the long run. However, at this point, online teaching has been a challenge for most staff and has essentially tripled our workload: it involves things such as recording lectures and generating subtitles, planning new types of activities adapted to online learning, updating our syllabus to ensure material is available online, etc.. We would still rather teach online not because we are not willing to leave our (however challenging) home offices, but because we prioritise the safety of our students and local communities.

Both teaching settings come with accessibility issues. However, we think that these are exacerbated in the current circumstances for in-person teaching, which will not be able to go ahead ‘as usual’ in any case (Isn’t in-person teaching a better experience for students?). When students are physically distanced in a large lecture theatre and when teaching staff are wearing masks, students with hearing impairments will be disadvantaged. Significantly, many universities have not provided reassurances to students with underlying health conditions or vulnerable relatives living with them.

Go to the list of questions ->>>

Isn’t in-person teaching a better experience for students?

University managements across the country are pretending that students can have an almost-normal university experience amidst the pandemic. As university staff, we know this will not be the case even if in-person teaching goes ahead. While online teaching, especially online teaching that arrives suddenly after a lockdown is announced, is not perfect, we think it is the better alternative to the existing in-person teaching plans. For instance, with social distancing measures, small-group work that is vital for many subjects is impossible in an in-person setting. Similarly, the informal chats between staff and students after class will not be possible, due to the necessity to stay distanced and vacate rooms as soon as the class finishes. Between wearing masks and staying one or two meters apart, this creates serious accessibility issues for many, including students with hearing impairment. Though online learning comes with concerns of isolation and anxiety, in-person teaching during the pandemic may also increase the stress and anxiety felt by students, especially those with underlying health conditions that put them at increased risk.

This all stands in a context in which the move to online teaching during term is likely. We think that committing to online teaching before a major outbreak is not only the safe option for staff, students, and communities but would also mean that staff can focus their attention on one teaching mode, rather than preparing for three options (Universities have had all summer to prepare safe teaching environments. Has this not been successful?).

Go to the list of questions ->>>

What about activities that can’t take place online, like labs and practical classes?

Warwick UCU’s position is that online teaching should be the default, but that activities impossible to conduct online – such as lab work – could go ahead in person with proper social distancing measures. With only the minimum of people coming to campus when strictly necessary, it will be safer for those that do come. Strangely, some departments have been informed that seminars or supervision meetings (which could go ahead online easily) should be done in person, but that lab work will be cancelled for the entire year!

We wish we knew more too! Universities aren’t providing information and they are not working enough with their teaching staff. So a few days before the start of term, we know about as much as incoming students. University management should have planned for this long ago.

Go to the list of questions ->>>

Why don’t you find a better way to split the workload among staff to allow for safe in-person teaching?

Many university staff are overworked as it is, especially those that are teaching. The workload of staff was already immense before the pandemic, which was one reason behind the strike in the last academic year. In 2019, the Guardian wrote about the mental health crisis amongst university staff, which was quoted to be mainly due to excessive workloads. These workloads were further exacerbated by the recent cuts especially to casualised teaching budgets. At Warwick, university management decided to cut the budget for casualised teaching staff, such as seminar tutors, by at least 50%. These casualised teachers deliver the vast majority of teaching at Warwick, so cuts to this budget mean that far fewer staff are available to teach compared to previous years (You mentioned casualised teachers. What does casualisation mean, and how does it affect me? ). The lay-offs were justified with the claim that a reduction in student numbers would put university finances under strain. However, we now know that universities underestimated student numbers in the new academic year – indeed, Warwick is expecting a surplus of students.

Another problem is that there aren’t enough classrooms large enough to accommodate safe in-person teaching either. Many rooms and corridors do not allow for social distancing and adequate ventilation, and accessibility issues are not addressed sufficiently. These issues in university managements’ planning also led to their announcement of longer teaching days, from 8am to 9pm at the University of Warwick, which will be problematic for students and staff with caring responsibilities and/or additional jobs. All of these problems were clear before the A-levels result fiasco, which led the university to take in more students than expected, leaving us at a guess of how this increase in numbers will be managed!

Go to the list of questions ->>>

Warwick is a campus university; shouldn’t that make it safer?

The Warwick campus is affectionately referred to as a ‘Warwick Bubble’ for its self-sufficient amenities and geographical distance from local neighbourhoods, but life at Warwick is far from concentrated just on campus. Most of our 28,000 students live off-campus. Many students also rely on off-campus employment to finance their studies. Staff also live across the country, including Leamington Spa and Coventry but also Birmingham, Oxford, London, or further afield and they commute to work on a daily basis. The geographical distance of the university from nearby areas does not deter the flow of people, which is unfortunately what contributes to spreading the virus. (Universities have made a commitment to in-person teaching. Why are you against it?)

Go to the list of questions ->>>

Wouldn’t online-only teaching mean massive job losses at universities?

It is ironic that massive job losses already happened at universities, and online-only teaching contributed very little to it. Numerous fixed-term and hourly-paid staff were laid off over the past few months, because universities claimed that they would be under financial strain due to reduction in student numbers. Now we know that they were wrong in underestimating how many students would go to universities in the new academic year. If universities really care about online teaching quality, they should indeed bring back the jobs previously lost due to their financial short-sightedness rather than cutting even more (You mentioned casualised teachers. What does casualisation mean, and how does it affect me? ). This of course should also count for the 50% reduction in the sessional teaching budget at Warwick, given how instrumental seminar tutors are especially for earlier years.

Go to the list of questions ->>>

You mentioned casualised teachers. What does casualisation mean, and how does it affect me?

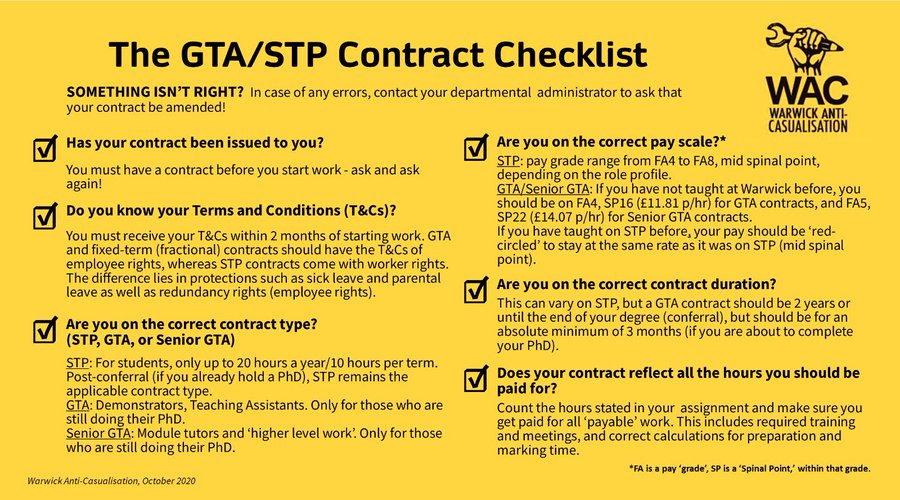

Casualisation means that fewer and fewer contracts are permanent, with most of the workforce now on temporary or hourly paid contracts. This has various negative implications. Employees on these contracts do not have job security, and often have to work across various contracts and institutions to make ends meet. Many are denied benefits such as pension or sick pay. Casualisation is embedded into the wider trend of marketisation in the higher education sector. Rather than being run as public services, universities are increasingly understood as businesses whose purpose is to make money. At Warwick, it has been implied by the University Council that sessional tutors, who are casualised workers, do not even provide work at all. Yet, it is sessional tutors who often have the closest interactions with students, and who provide a bulk of teaching, especially at the University of Warwick.

You should care because this trend can not only lead to a deterioration of working conditions but also learning conditions. When teachers have to move to a new contract every year and are not paid over the summer, that means that they have less time to focus on the design of modules. We think that university managers should invest into their teaching and research staff, rather than in astronomical salaries for management and consultants or vanity projects and shiny new buildings. The current pandemic has not created these problems, they have existed for years. However, it has exacerbated them and made them particularly visible, for instance through the mass layoffs of casualised staff. Covid-19 has underscored how unsustainable, unfair, and detrimental to knowledge generation casualisation is.

Go to the list of questions ->>>